Intro

Intro

The key role development financial institutions played in achieving global sustainable development and its environmental and social responsibilities have been discussed in the previous issue. Apart from providing stable and long-term financial support, development finance should also establish a standardized market operational mechanism as well as improve policies implementation of environmental and social safeguards, to set a new financing model friendly to the society, environment and climate. Besides, an independent accountability mechanism for project-affected stakeholders should be set up as a responsible effort to reduce negative impacts, ensure long-term benefits of its investment, respond to the project complaint and provide rights relief. Such mechanism is generally called grievance mechanism.

Grievance mechanism is a formal, legal or non-legal (or judicial/non-judicial) complaint process that can be used by individuals, workers, communities and/or non-governmental sectors that are negatively affected by commercial activities. Grievance mechanisms are also called 'dispute' 'complaints' and 'accountability' mechanisms. They can be set up by companies, financial institutions, or organisations at national or international level. Some mechanisms directly supervise companies while others fulfill governments’ obligation to protect citizens from human rights violations by third parties. The WB, ADB, EBRD and development banks of major countries in the world have already established independent grievance and accountability mechanisms. International groups and experts also suggested that the AIIB should set up an independent grievance and accountability mechanism. Grievance mechanism and its international practices will be introduced in this issue.

![]() Key Point

Key Point

The investing and financing process of international projects would usually involve a series of complicated issues which have to be confronted, such as environmental resources exploitation, land acquisition, resettlement and compensation and cultural heritage. Any mishandled issue and link may lead to controversy or dispute and even finally affect progress of the project, causing economic loss. How to avoid and properly resolve environmental and social disputes in international financing projects has become a question closely watched by bilateral and multilateral international financial institutions, governments, local communities of project-based region and civil societies.

In order to avoid and property resolve environmental and social disputes in international financing projects to ensure the long-term benefits of investment and demonstrate their responsible attitude, international financial institutions such as the World Bank and ADB firstly made high-standard environmental and social safeguard policies and made revision and improvement to such policies continuously. In 2012, the World Bank launched update and revision work on its environmental and social safeguard policies to strengthen the sustainability of the financed projects by continuously encouraging the participation of stakeholders. In July, 2015, the CODE under the World Bank’s Board of Executive Directors conducted the 3rd-phase consultation for discussion of the second revised draft of Environmental and Social Policies. Now the 3rd-phase consultation ended. In last September, the AIIB also disclosed the draft of its Environmental and Social Framework and the subsequent consultation procedure also attracted extensive focus and discussion among international community. The new Version of ESF was disclosed at the end of February.

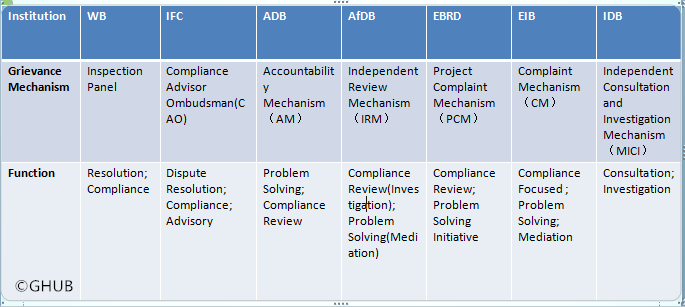

Apart from making and improving high-standard safeguard policies, the development financial institutions also set up independent grievance mechanisms to address project-related complaint to protect local citizens in invested regions from being negatively affected by the project and their rights from being infringed. Under the World Bank, there is the Inspection Panel, an independent complaints mechanism for people and communities who believe that they have been, or are likely to be, adversely affected by a World Bank-funded project. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) under the World Bank also set up an independent accountability agency on environmental and social affairs, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), to help resolve issues with environmental and/or social impacts incurred from projects supported or participated by IFC and MIGA. The current ADB accountability mechanism (AM), having taken effect since 2002, includes two independent offices, the SPF responsible for the problem solving function and the CRP responsible for compliance review. Through the AM, the stakeholders directly or indirectly affected by ADB-financed projects could file complaints with the ADB. The Following picture gives a brief information on the courrently existing grievance mechanism in multilateral development financial institutions.

What is a grievance mechanism?

A grievance mechanism is a formal, legal or non-legal (or ‘judicial/non-judicial’) complaint process that can be used by individuals, workers, communities and/or civil society organisations that are being negatively affected by certain business activities and operations. Grievance mechanisms are also called ‘dispute’, ‘complaints’ and 'accountability' mechanisms.

A wide variety of grievance mechanisms exist at the project, company, sector, national, regional and intergovernmental levels. They vary in objective, approach, target groups, composition and government backing. They also vary in how long the procedure can take to conclude and whether there are any costs involved. They may be set up by companies, financial institutions, organisations at the interstate level or at the international level. Some mechanisms directly address companies while others address states' responsibility to protect citizens against human rights violations by third parties.

What types of grievance mechanisms exist?

The manner in which grievance mechanisms deal with complaints also varies widely. Some are designed to resolve problems through dialogue-based, problem-solving methods like mediation. Others conduct investigations or fact-finding that leads to recommendations or statements. Finally, some mechanisms are mandated to attach consequences to their findings, such as delisting, withdrawing funds or excluding access to government benefits. But some grievance mechanisms have more functions. For instance, the CAO responsible for dealing with complaints with the IFC has three functions of dispute resolution, compliance investigation and advisory, while the ADB accountability mechanism includes two independent offices, the SPF responsible for issue solution and the CRP responsible for compliance review. The Inspection Panel of the World Bank serves as an independent dialogue platform to provide stakeholders of projects financed by the World Bank with opportunities to voice their grievances. The Inspection Panel investigates the complaints on whether the World Bank has followed its own policies and procedures in project designing and implementation. In case of policy violation found by the Inspection Panel, the World Bank will rectify its action and deal with relevant damages according to investigative findings of the Inspection Panel.

What are the costs of using grievance mechanisms?

Grievance mechanisms do not typically charge fees, and some may provide financial assistance to complainants to help them engage in the process. However, the process of filing a complaint with a grievance mechanism can still be costly for complainants. However, given the wide variety of mechanisms that exist, it is difficult to provide estimates of how much filing a complaint with a grievance mechanism could cost.

Whether you are a group of affected individuals or an organisation, preparing a complaint will require an investment of your financial and human resources. After the complaint has been filed, you will need the resources to coordinate with the affected individuals and any local, regional or international partners. You may have to respond to requests for additional research and information, which could incur further costs. In addition, you may have to cover travel expenses to participate in meetings. Despite these expenses, filing a complaint with a grievance mechanism is usually still cheaper than taking legal action.

Who can file a human rights complaint?

As a general rule, grievance mechanisms accept complaints from affected individuals, groups and/or their representatives provided the raised issues raised fall within the scope of the mechanism and the case meets applicable eligibility requirements. Individuals may include human rights activists, workers, trade unionists and community leaders. Groups may include trade unions, peasant associations, local communities, indigenous peoples, social movements and/or civil society organisations. For example, any individual, group, community, or other party can make a complaint to CAO if they believe they are, or may be, affected by an IFC or MIGA project(s). Complaints may be made on behalf of those affected by a representative or an organization.

Specific requirements of complaint procedures

Each grievance mechanism may have specific eligibility requirements that must be met before a complaint will be considered. For example, some labour-related mechanisms will only accept complaints submitted by trade union organisations. Other mechanisms will only accept complaints from project-affected people or workers. There may also be specific requirements regarding a complainant’s so-called 'interest' in the matter if the complaint is filed by a person or group that is not directly affected by the corporate activity.

Jointly filing a complaint against a company

Complaints are often filed jointly by a number of individuals or groups in national or international coalitions for reasons of standing, international solidarity and relevant expertise. Complaints filed jointly by individuals and groups may also help to increase awareness of the issues nationally or internationally.

According to CAO, the complaint must relate to a social or environmental impact of an IFC- or MIGA-funded project; it must show that the individuals submitting the complaint have been or likely will be affected by social or environmental impacts on the ground.

Where to find help with filing a complaint?

The process of filing a complaint with some mechanisms can be demanding and complicated while others can be relatively easy and straightforward. SOMO has extensive experience in helping groups to prepare complaints. SOMO can help you to choose the most appropriate grievance mechanism, and help you to identify and understand the relevant social and environmental standards and principles that may apply. SOMO also provides support in identifying experts with specific expertise and experience with a particular grievance mechanism.

There are many other organisations with experience using grievance mechanisms that may be able to provide advice and support as well.

Africa:

Action contre l’impunité pour les droits humains (ACIDH)

Civil Society Research and Support Collective (CSRSC)

Asia:

Business Watch India (BWI)

Workers’ Assistance Center (WAC)

Latin-America:

Centre for Reflection and Action on Labour Rights (CEREAL)

Europe:

Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID)

How long does it typically take?

Some complaint processes can be completed within months while others may take a year or more. There are a few mechanisms that can take many years to conclude. When determining whether to file with a particular grievance mechanism, you should consider the mechanism’s record of accomplishment in this regard. If the process is likely to take a year or more, it is advisable to assess whether you have the resources to sustain your engagement. It will usually take CAO more than a year to handle a case, starting from tghe point when CAO accepts the case. For instance, the case, Chile / Empresa Electrica Pangue S.A.-02/Upper Bio-Bio Watershed, took CAO nearly eight years to finally close, lasting from October, 2002 to 2010.

Advantages of non-judicial grievance mechanisms

A complaint may prevent, terminate, mitigate and/or remediate harmful business activities. Some grievance mechanisms can recommend or require specific remedies for the victims, or if it is a problem-solving process, remedies could be agreed upon by the parties. Grievance mechanisms may also involve official fact-finding processes and policy compliance reviews.

Filing a complaint may also help to generate public awareness and media attention, which is often needed to persuade decision-makers such as politicians, investors and other key stakeholders to take action in your favour. A successful grievance process could also lead to better policies and practices by the company or even set a new standard of best practice for similar projects or a sector.

Limitations of non-judicial grievance mechanisms

On the other hand, many challenges exist in the functioning and effectiveness of currently available grievance mechanisms. Many fail to meet basic performance criteria such as accessibility, predictability, equitability, transparency and independence. Others may take an excessive amount of time to resolve complaints, and some have confidentiality rules that might limit what issues can be discussed publicly if mediation is on-going.

In addition, the effectiveness of many grievance mechanisms depends on the willingness of the company to be involved in the process. There can be too many procedural hurdles for complainants to navigate before their issues are actually addressed. While some mechanisms have procedures in place to protect complainants against retaliation, most do not. The process of filing a complaint can also be very time-consuming and resource-intensive. Lastly, many mechanisms cannot issue binding recommendations and even fewer have the ability to enforce outcomes. This means that, even after the process concludes, there is no guarantee the company will actually change its behaviour.

Non-judicial grievance mechanisms versus legal action

Non-judicial grievance mechanisms play an important role in complementing and supplementing the often more expensive and time-consuming legal forms of addressing corporate misconduct. However, non-judicial mechanisms are no substitute for legal action, and severe human rights abuses should still be taken to court whenever possible.

However, affected groups or communities may have legitimate reasons for their lack of faith in the fair and timely treatment of their case in domestic courts. Often there are also financial obstacles to pursuing legal action. Non-judicial mechanisms, while time-consuming, may cost less than taking legal action.

It is important to keep in mind that some grievance mechanisms will not consider complaints if there are parallel legal or other types of proceedings pending. On the other hand, cases filed with a non-judicial grievance mechanism may cover a broader range of issues than those dealt with in the courts, legitimising their parallel handling in non-judicial forums.

Examples of GMs:

The CAO was created in 1999 to receive complaints from communities that were harmed, or may be harmed, by IFC and MIGA activities. Its mission is to address community concerns about IFC or MIGA-funded projects, enhance environmental and social outcomes on the ground, and provide transparency and greater public accountability of IFC and MIGA.

The CAO has three functions:

- To assist communities and companies to resolve their disputes (Dispute Resolution),

- To determine whether the IFC and MIGA complied with their rules when conducting due diligence (Compliance Investigation), and

- To provide advice to the World Bank Group (Advisor).

The CAO’s Dispute Resolution function provides a forum for communities and companies to address grievances, but only if the company agrees to participate in the process voluntarily. Even when companies agree to participate, if they do not enter the process in good faith, it is unlikely that they will make meaningful progress towards addressing a dispute. If one or more of the parties choose the Compliance function, or if the parties are unwilling or unable to reach agreement through dispute resolution, CAO’s Compliance function will be initiated.

The head of the CAO is called the CAO Vice President. The CAO Vice President reports to the President of the World Bank Group. The CAO staff is composed of individuals appointed by the CAO Vice President. To encourage the CAO’s independence, staff members are prohibited from being employed by either the IFC or MIGA for two years after they have ended their term at the CAO and the CAO Vice President is restricted from ever being employed by the IFC or MIGA in the future.

Submitting a complaint to the CAO could:

- Help raise the awareness of what is happening, both locally and internationally;

- Allow you to directly voice your concerns to the IFC and MIGA about a project;

- Allow for direct dialogue with the project company through a Dispute Resolution process if the company agrees to participate in the process;

- Lead to a formal investigation through a Compliance Investigation to determine whether or not there have been violations of IFC and MIGA rules;

- Lead to public monitoring and reporting on any violations of IFC or MIGA rules;

- Lead to action by the WB Group leadership to correct the violation.

Submitting a complaint to the CAO cannot:

- Guarantee that harm being caused by an IFC or MIGA supported project will be stopped or prevented;

- Force a company to participate in a voluntary Dispute Resolution process; if a company refuses to cooperate, the Dispute Resolution process ends;

- Lead to attribution of blame or lead to findings that a company or the IFC is “guilty”;

- Guarantee that the CAO will conduct an investigation.

OGMs

What are OGMs?

Operational-level grievance mechanisms (OGMs) are systems that companies set up at their operational sites to handle environmental and human rights complaints and concerns from workers, community members, and other stakeholders that have been affected by company operations. Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which have been endorsed by China, companies are advised to have a non-judicial complaints process in place at the project level, to serve as a constructive and more efficient alternative to handling complaints through the courts.

Despite a company’s best efforts, negative impacts of operations and projects do occur, and grievances may arise among affected communities around the implementation of a project. OGMs can offer a variety of remedies and dispute resolution options, including victim compensation, injunctions, company-community dialogue, brokered agreements, and investigation of complaints and allegations. They can enable disputes to be resolved quickly at the project level, before they escalate to more protracted disputes resulting in claims filed in the courts or other forums.

There are multiple forms that OGMs can take, and each company OGM will likely vary in its operating procedure to be compatible with the local context it is operating in. OGMs can be community-driven, where affected populations design and implement the mechanism as informed by local context and expectations, as well as international standards. Companies can also play a larger role in shaping the mechanism, and can further encourage suppliers and contractors to develop their own OGMs in order to reduce risks associated with company operations. Companies have the flexibility to design separate grievance mechanisms for project workers and external stakeholders. OGMs can work independently from, or together with host country administrative procedures and state-based grievance mechanisms, and where no decision is reached through an OGM, traditional state procedures can be relied upon for decision-making and resolution of disputes.

OGMs help create a stable business climate and predictable forum that communities view as legitimate by providing a local and often simpler supplement and/or substitute to judicial remedies. In many parts of the world, companies have seen tensions escalate and community relations deteriorate in large part due to a communities’ inability to articulate and seek remedies for the human rights and other concerns that arise in connection with company operations. OGMs provide an important alternative for airing complaints and accessing justice in high-risk host countries, including those with underdeveloped environmental and social safeguards, and weak, remote, and slow legal and administrative systems that are not trusted by local communities.

OGMs can provide faster and more flexible remedies than the courts through a process in which the company has a constructive—rather than oppositional—role, thus preventing problems from escalating and promoting a more positive relationship between companies and communities. OGMs have the added benefit of improving morale in workers and the community, and protecting against political and reputational risk to ensure the long-term viability and sustainability of companies and their operations.

In addition to reducing social, political, and legal risk, a well-designed OGM can reduce financial risk and save companies money by identifying problems early on, and enable them to operate more smoothly in the community context in which they are embedded. They can do so by facilitating the development of mutually agreed upon solutions to problems, whereby both company and community priorities are considered. Early identification of problems can reduce and preventing costs associated with conflict, such as litigation, increased security, public protests, employee strikes, and suspension of operations.

Alert

Alert

- Pressure mounts on AIIB for greater clarity on green lending

- Investigation Announced into Harm Caused by Inter-American Development Bank-Funded Airport Expansion in Colombia

- OECD Brochure on Responsible Business in Conflict Settings

- Joint Submission from Civil Society on Accountability in AIIB

- AIIB to set up high-standard, feasible safeguard policies

- Green safeguards yield higher economic returns

View

View

Yu Xiaogang Green Watershed:"AIIB needs to implement additional measures to ensure greater transparency and accountability. This should apply project-by-project, and will benefit the future development of the bank."

Jeff Tyson Global Development Reporter for Devex:"One important thing to understand about how the Inspection Panel works is that it investigates relatively few of the cases it receives. In fact, of the 104 total complaints the panel has received since its inception, just 34 to-date have been investigated. One reason that the Inspection Panel may decide not to pursue a formal investigation of a case is if the panel considers World Bank management’s response to a complaint and management’s proposed plan of action to be adequate."

International Institute for Environment and Development Dispute or dialogue? Community perspectives on company-led grievance mechanisms:"Company–community grievance mechanisms play a very particular role, not least in the extractive sectors. They are often closest to the point where impacts actually occur. Where these mechanisms work well, companies can identify complaints early and remedy them before they escalate into more serious issues. They can do so in a manner that reflects local needs, preserves relationships and avoids or reduces harm to human rights. Additionally, both the policy debate and practice would be highly enriched if there were clear and tested metrics for measuring effectiveness of grievance mechanisms. Unfortunately, here again the literature is limited."

Earthrights International Operational-level grievance mechanisms (OGMs):"OGMs can create transparent and concrete processes and outcomes that lie in direct contrast to the legal systems of many high-risk countries. Especially when systems are developed with community input, such transparency can in effect give the company a “social license” to operate in the community, through which companies gain trust and increased reputation, both locally and internationally. Communities can be less likely to resort to other alternatives, such as violent conflict and protest when there are legitimate forums to air their grievances. Communities may also be more likely to access OGMs prior to traditional state-based grievance mechanisms that are viewed as corrupt and ineffective, and in doing so, notify companies of alleged abuses before tensions escalate and last-resort forms of raising grievances are used. OGMs provide forums to identify problems early on and receive clear outcomes. OGMs benefit companies by granting them more control over dispute-resolution processes and by reducing the possibility of resort to third parties or host-countries’ opaque and underdeveloped legal systems."

Resource

Resource

- Report: Compliance Advisor Ombudsman(CH)- Greenovation Hub

- Report: An Overview of International Standards for Responsible Business in Conflict-affected and Fragile Environments- the International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding

- Report: Amplifying Voices, Defending Rights--2012–2015 Report of Accountability Counsel- Accountability Counsel

- Brochure: World Bank Inspection Panel brochure- Centre for Research on Multinational corporations& Accountability Counsel

- Brochure: The Asian Development Bank’s Accountability Mechanism- Centre for Research on Multinational corporations& Accountability Counsel

- Guide: A Guide to Designing and Implementing Grievance Mechanisms for Development Projects- Compliance Advisor Ombudsman

- Guide: Accountability Resource Guide - Accountability Counsel

- Website: International Labour Organization’s Committee on Freedom of Association- International Labour Organisation

- Website: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Project Complaint Mechanism

Case Study

Case Study

Chile / Empresa Electrica Pangue S.A.-02/Upper Bio-Bio Watershed

1. Project Information

Institution: IFC

Project Name & Number:Empresa Electrica Pangue S.A. 2067

Department: Infrastructure

Company: Empresa Electrica Pangue S.A.

Sector: Utilities

Region: Latin America & the Caribbean

Country: Chile

Environmental Category: A

Commitment: 2.5% (Equity Interest) & $170 million (Loan)

2. Complaint

The Pangue Hydroelectric Project involved a series of proposed hydroelectric dams on the upper BioBio River, Chile. In July 2002, a group of Pehuenche women lodged a complaint with CAO in relation to the following concerns:

1. Inappropriate and weak social and environmental mitigation measures; and

2. Lack of adequate compensation for those individuals affected by the project.

IFC held 2.5 percent of the equity interest in the Pangue Project from October 1993 until divestment in July 2002. As a result of various complaints lodged by local groups and NGOs at the time of dam construction, the President of the World Bank Group seconded Jay Hair, President of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, to undertake an independent inquiry into the complaints, which became known as the Hair Report.

3. CAO Action

Despite divestment in 2002, CAO accepted the complaint based on the fact that the complaint related directly to IFC’s role in the project over a number of years; to promises and commitments made; and to previous opinion by independent investigations and consultant reports requiring certain actions be undertaken by IFC. In July 2002, CAO Compliance conducted an appraisal for audit of the project and commenced assessment in October 2002.

4. Status

The Appraisal Report, completed in May 2003, recommended that IFC disclose the Hair Report and disseminate documents it had commissioned including emergency response plans and downstream impact studies. At the request of the complainants, CAO Ombudsman continued to monitor the settlement by working with local and indigenous organizations to address broader, cultural impacts of the project. In February 2006, a settlement agreement concerning local development capacity building was finalized and CAO continued to monitor implementation of this agreement. The following picture shows the whole process of this case:

![]()

5. Reports Related to the Case:

Assessment Report(s)

Assessment Report, Regarding IFC's Investment in ENDESA Pangue S.A., May 2003

Agreement(s)

Pangue Complaint Settlement Agreement between CAO and UNIMACH, February 9, 2006

Close-out Report(s)

Historical Summary, We Monguen (Indigenous Community Center), May 25, 2010

CAO Conclusion Report, Pangue Hydroelectric, June 2010

IFC Lessons Learned: Pangue Hydroelectric (Summary), November 2004, IFC

Compliance

Appraisal Report(s)

There are no documents currently available in this category.

Audit Report(s)

There are no documents currently available in this category.

Monitoring Report(s)

There are no documents currently available in this category.

Observation on China's Overseas Investment wishes to present multiple views and perspectives to enhance understanding concerning China's overseas investment and global footprint, so as to promote China's "going out" in a more responsible and more sustainable way.

We welcome experts and scholars sharing related cases and views with us.

Please send us your comment to policy@ghub.org.

We welcome your feedback and will share some selected insight upon permission in next issue.